Blog Post # 5 | Antoneisha Dunn | November 14, 2023

I stood with my sister, our hands interlocked in a tight grip, the warmth of her palm melding with mine as we faced our aunt’s sister on the wooden-framed veranda. We had spoken with her before, but today the air was heavy with tension: thick enough to cut with a knife. The sun, casting a golden hue over the scene, painted shadows on the veranda floor. As we stood there, a growing unease coloured my sister’s responses, and I suppose they matched the growing annoyance that settled along our “aunt’s” brow. “Yuh cyaah chat patois!?” Aunt Tes blurted before my sister finished her sentence. Evidently puzzled and hurt, my sister laughed, completed her sentence in English, and tugged at my hand as she turned towards the road.

“Bye, Aunty Tes” she added as we left the place where we stood for home. Aunt Di’s house was one of the places my sister and I visited. Her house was newly built and smelt of paint and bleach. The yard’s space was moderately sized and manicured often to maintain the prestige our aunt projected. But like all impoverished communities, her newly built wooden house stood in contrast with the others around it. I am not sure our Aunt Di realized how similar she was to the environment from which she was trying to disassociate. Neither do I think she realised how the culture of the community resided within her home: within her sister who recently moved in.

On that day, when Aunt Tes blurted “Yuh cyaah chat patois,” I knew the contradiction my sister represented to the life that “aunt” left behind in the ‘country:’ the communication she was used to. I suppose my sister’s choice of language unsettled her, and reinforced the gap between where she now lived and where she came from. Children of a similar age to my sister and me only spoke the vernacular in the country, so my sister was an anomaly that aunt didn’t want to entertain: that day at least.

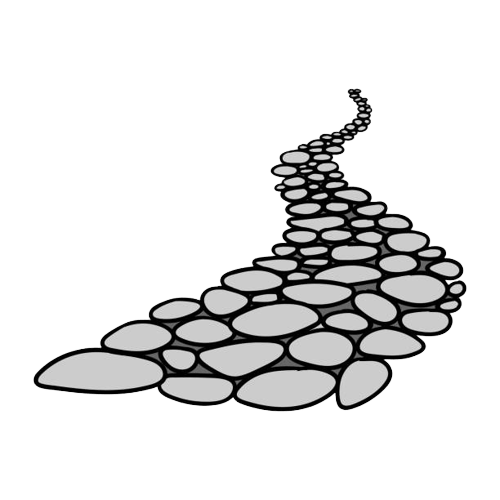

As we walked the stony, desired path towards home, silence fell between us. We did not talk about that “aunt’s” outburst and what it might have meant. But then again how could we when we were only kids. As we walked, the dust kicked up from our feet propelled petals onto the zinc fences that separated houses from us. The air was cool, and a wisp of wind hummed an untold melody as we hurried along. Our march was militant, our gait steady, our thoughts everywhere; at least so it was until we saw home.

That single-roomed structure seemed to welcome us in. We passed our neighbour’s house and walked onto the part of the land our mom built our home. It, our home, was the refuge from the assaults we faced within the world. It was where we felt free to be ourselves. It was where all the versions of ourselves were donned. There, within that older wooden and mutely painted structure, my sister knew her use of Jamaican English would be accepted. There, within the structure that matched the community’s in age and style, my sister and I were able to be the difference our aunt’s house represented.

Leave a reply to jessiemayers Cancel reply