Antoneisha Dunn | Blog #3 | October 14, 2023

When I was a tenth grade student, my language teacher shared with me the belief she had regarding creole as a vulgar and substandard language. I had stood there talking with her, and for reasons unknown to me, I code switched. I hadn’t said a sentence, before she interrupted me with: “you sound ghetto and brawling when you speak patwah.” I believe she followed up that statement with a request that I reconsider using the vernacular. Something in the disgust that settled across her face, made me feel small and inadequate. Moreover, and in a bid to win her approval, I worked hard to limit as well as eliminate creole from use. Over time, this mindset of hers echoed through my experiences at the University of the West Indies (UWI), where I found myself struggling to embrace the rich heritage of Jamaica’s vernacular, even in simple tasks like singing folk songs with my peers.

Unfortunately, my teacher’s viewpoint regarding creole wasn’t an isolated incident. During my studies in a course on “Teaching the Structure of English,” I encountered a prevailing trend among scholars and influential figures to dismiss the communicative and linguistic value of Jamaican Creole (JC). Shockingly, even some younger members of our society failed to recognise JC as a distinct language with its own set of syntactic, semantic, and phonological rules akin to English. The prevalence of this negative and contradictory attitude is largely fuelled by the widespread fallacy that creole lacks its own well-defined linguistic structure and is merely a debased version of English, with limited significance.

In one book entitled “What Do Jamaican Children Speak,” the author Michele Kennedy discusses the complex attitude that the wider public has towards creole. She spoke about the appreciation some Jamaicans have of the expressive features of the vernacular. She even mentioned how creole is viewed in some parts of the Caribbean as “the language of friendship, identity and solidarity.1” Conversely there are members of our speech community who think creole is a lesser and disreputable language. So low is the status of the vernacular, that some feel it inappropriate to use it to talk to God!2

Morris Cargill further debased the language within his 2000 article when he assigned it parity with the barks of his poodle. According to him there are a variety of creoles among which is “Poodle Creole” a language he sarcastically called “poodlese”.3 More than this, he considered some creoles to be nothing more than “primitive jabbering;” and as if echoing the sentiments of a subset of the population he categorised creole “under the heading of speaking badly.” What I found the most appalling, but relatable, is the correlation he made between language use and individual currency. According to him an individual’s value is improved when he swaps JC out for English.

In light of the aforementioned evidence, I have come to see that the lie hinted at earlier is more wide-spread than I previously believed; and that my language teacher was representative of a number of Jamaicans who assign lesser value to the language of the majority. There is even an ambivalence that exists among the speakers of JC and Jamaican English. This ambivalence is described by Kennedy as something that is both complex and contradictory. But, none of the texts I have read have likened these beliefs to conspiratorial myths.

Until now.

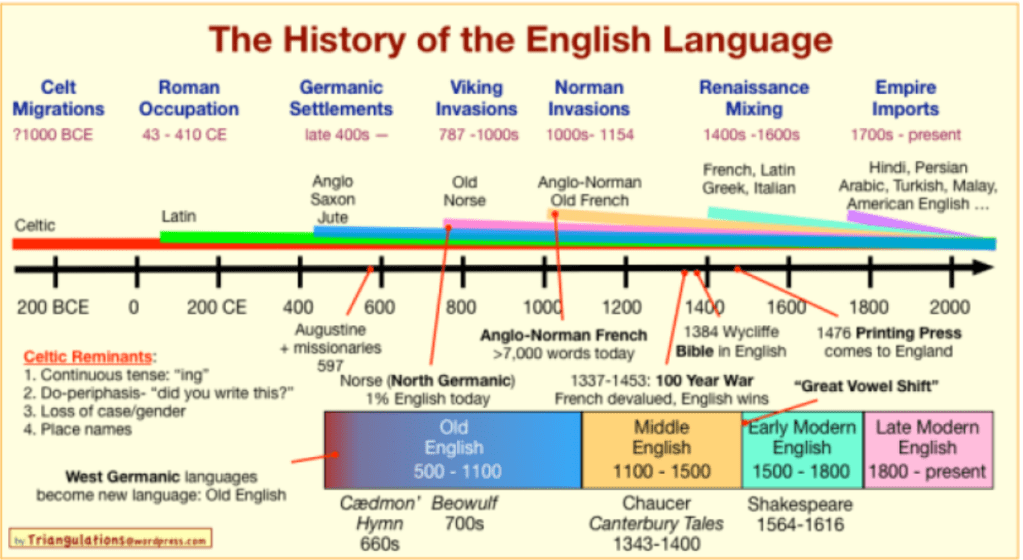

It is worth noting that English, once marginalised and disdained, underwent a similar process of ostracisation. Few are aware that it was originally the language of the majority before attaining institutional prominence. The historical shifts that transformed English into a global lingua franca mirror the development I seek to highlight for Creole in my project. The incorporation of loan words from diverse languages into English history underscores the intricacies of language evolution and the need for a comprehensive understanding of creole’s development within a historical context. But, how can one account for the ignorance many have of English’s growth to prominence? The answer is: historical amnesia!

The oversight of how English itself transitioned from a marginalised dialect to a globally respected language suggests a broader ignorance of the complex historical processes shaping linguistic identities. Understanding the struggles and transformations that elevated English to its current esteemed position provides a crucial lens through which the creoles of the region, including Jamaican Creole, can be more profoundly appreciated. Acknowledging that English, too, was once subjected to similar derogatory judgments and societal biases underscores the need to contextualise the development of creoles within a historical continuum. Embracing this historical perspective not only cultivates a deeper appreciation for the linguistic richness inherent in the creoles of the region, but also serves as a powerful tool in debunking the entrenched prejudices that undermine their rightful recognition and respect. It is through this conscious reevaluation of history that a more inclusive and holistic understanding of language evolution and cultural identity can emerge, fostering a climate of appreciation and celebration for the diverse linguistic tapestry woven within the Caribbean.

And this reevaluation is what my contribution to the group project seeks to do!

Years after that exchange with my language teacher, I have come to see creole as a language like any other; with its own rules and systems. It has its own mechanisms for pluralisation, tense, possession and concord. More importantly, it has speakers whose communications are as complete as any other. And in hindsight, it is clear that my teacher’s perspective on Creole was fundamentally flawed.

- Kennedy, M. (2017). What do Jamaican children speak? UWI Press.

↩︎ - Kennedy, M. (2017). What do Jamaican children speak? UWI Press. ↩︎

- Durrleman , S. (2008). The Syntax of Jamaican Creole. John Benjamins Publishing Co. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.127 ↩︎

Leave a reply to jessiemayers Cancel reply