by Blaire Santos | 20th December, 2023 | Extended version of the short story, Blair Atoll

“Grandma, me an Blaire wahn si Daddy.”

“Aarait, Brods. Blaya!” she yelled, unable to pronounce my name. “Go bring di foan.”

I stretched coiled wire ringlets until the house phone reached Grandma’s hand, then went back to the base and pushed the familiar sequence of grey buttons.

“Bernard, Ah di bring di pikni dehn fi kohn si yu.”

Soon, the exhaustive sigh of the Mazda 626 sedan heralded another trip. Back then, the trip from Belmopan took four hours. Winding along the Hummingbird Highway, the sedan strained up the slippery slopes of the Maya Mountains that called down rain every day until the rainforest dissolved into pine. Back then, the asphalt gave way to red dirt at the start of the Southern Highway, more potholes than highway. Dust congealed on the Mazda’s metallic teal, matching the metal sign pegged at Blair Atholl, the shrimp farm where Daddy lived.

Between 1999 and 2003, Daddy supervised the construction of a 30,000-square-foot hatchery building, forty 20,000-gallon water tanks, each with sixteen perfectly even sides, a 500,000-gallon saltwater tank and fifteen 1,500-square-foot residences. Still, when everything started, there were just ponds—squares dug out from the sodden clay that never dries even on the hottest days. Between them ran muddy roads, narrower than the bridges of the Hummingbird Highway, where only one vehicle could cross at a time.

Finally, we reached the compound and parked outside Daddy’s Mennonite house.

“Daddy nayhn you afta wa shcrimp faam,” Brodam teased.

Not allowing time for the adults to exchange pleasantries, we rushed Daddy, giggling, cooing, fighting to get spoiled—to be scratched by kisses.

“Daddy, yu hyaa weh Brods seh? Yu neva nayhn me afta wa schrimp faam chu?”

“No Blaire, but A-Ah glad Ah p-put da ‘e’ pan yu nayhn. Miss Sofi, gyal yu noh e-eezi. Yu stil di c-cut bout.”

“Well yu noa, lang as Gaad willin mee an dis oal kaa ku goh eniway. Bwai, guess weh Ah bring fahn Belmopan.”

Grandma reached into her blue bag with pink roses and pulled out a finishing line wrapped around a stick and a box of black hooks. She packed them after he told her over the phone that the men saw a huge tarpon in one of the channels, and that no one could catch.

We went back into the Mazda, four of us this time. Daddy took over the steering wheel. We zoomed beyond the green squares of shrimp pens towards the pools of perfect cyan near the mangroves gripping the lagoon side of the Placencia peninsula. Sometimes, Daddy would watch us swim in them, our feet painting red streaks across the glowing blue with sediment stirred up from the bottom. But Daddy would always watch from the side. He could swim, but he’d seen a man drown once. He would say, “Mee da u-unu laifgyaad, and l-laifgyaad noh swim.” But that day, we went fishing—to watch Grandma in her glory.

Grandma put on her pink sombrero, took out a wooden step stool from the rusty trunk and settled on the bank’s clay, facing the mangroves across the narrow stream of bright blue.

“Miss Sofi, Ah da wahn w-wa hat l-laik dat,” said Daddy, eyeing the woven straws that matched the roses on her bag.

“Yu ku tek dis hat if yu wahn ahn, but yu noh worid dat dehn nada man wa teez yu?”

“Cho! Mee noh kayr bout dehn ting Miss S-Sofi. Ahn n-nobadi ku teez mee moa dahn Ah ku teez dehn.”

“Blaya!” she yelled. “Goh get mi nada hat fahn di kaa.”

“Yes, Grandma,” I said, running to fetch her largest sombrero from the car’s sombrero stash. My dash left imprints on the yielding ground, soft as maza. I wonder how that Mazda didn’t get bogged.

Breeze skimmed the taut surface of the deep like a phantom, leaving the smell of salt and mud with every intimate touch, and the blue waters shivered in response. The conversation had long died as the rhythm of fishing began. Daddy stood back, watching. He wasn’t a fisherman, but Brods and I flanked either side of the expert. She did not need a fishing rod. She did not even need to bring bait. She waved the line like a magic wand and conjured fish on the hook with a sharp diagonal tug of her burly hands. Brodam freed them from the hook only momentarily before deciding their fate. Snapper and bay snook would at least die whole, with dignity, even as he sliced open their bellies and scraped out their guts into the thin strip of sea. I chopped the others into chunks to attract the six-foot, hundred-pound titan, flaunting its treasure of argent shillings on its sleeve.

I don’t know where Daddy looked when the tarpon bit the line, but I know he didn’t see it. He didn’t see the silver shuttle fly towards heaven and sink into hell, trashing away all tranquillity in the boom of its flop. He only saw the blue turn white in a liquid pirouette.

“Ah gat ahn!” cried Grandma. She stood up, and Brodam braced her. He was only a year older than I, but he seemed twice my size. I looked back at Daddy, calling him over with the repeated bending of my fingers, but then I saw his eyes swell with panic under the shadow of the pink sombrero. His mouth parted and collapsed in an aquatic pulse. He stretched his hands towards me, opening and closing them, trying to grasp me, but his feet stuck to the ground. Then, the water thundered behind me. I felt its faint hiss. Daddy screamed, and Grandma lost her concentration, lost her tarpon, and Brods was yet a man.

Grandma yelled, “Bernard, da weh do yu? Yu fraitn weh di fish!”

“D-Da y-yu s-seh, ‘a-aligeta’!”

“Ah seh, ‘Ah gat ahn’!”

Shame took over his fear, followed by his cackles, which wheezed in and out like the Mazda’s ignition until we all laughed.

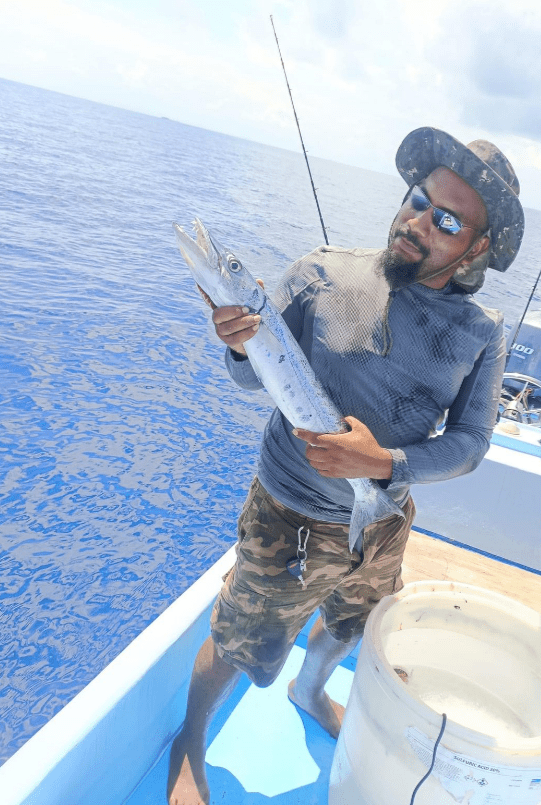

Years later, when Brods was also six-feet and at least double the weight of the fish we’d lost, he brought a huge tarpon for Grandma and me, and we ate fish every way—fried, boiled, steamed, baked—for weeks.

Brods and I planned a family fishing trip for Grandma’s eighty-seventh birthday. His fiancé, his son, his daughter, our big sister, her daughter, and our little brother—all nine of us would have gone. We would have stayed in Placencia, on the beach side without the mangroves, and taken a boat onto the perfect cyan sea and fish with rods, and bait, and everything. We would have driven past the clean Blair Atholl sign on the well-paved road and said, “Memba when Daddy mi tink Grandma seh ‘aligata’ insted a ‘Ah gat ahn’?” like we did every time we travelled that road.

But three days before the trip, Brods was killed right in front of his house—the house where we grew up with Grandma. He’d just renovated it. He moved in for less than a month with his family. He had his fishing rods arranged neatly by the door of the freshly painted screened-in patio with anticipation. His Dodge Ram was parked exactly where the Mazda once sat.

July 25, 2023, at 7:33 p.m., Brods texted me, “Tomorrow will be better.” It was the last message he ever sent me.

At 8:30 p.m., His fiancé, Domz, called me. I couldn’t understand her initially as I only picked up the choked sounds of inconsolable tears. She needed help to take Brods to the hospital because two men on a motorcycle had sped by and shot him, and he was too heavy for her to carry.

At that moment, I remember feeling calm. Unworried. Brods had been shot once before, in his face, at point-blank range. On December 27, 2019, he left my house after a games night where the only dish served was pumpkin soup, which he was not particularly fond of. So, he pulled up to a popular restaurant to get some rice and beans on his way home. The parking lot was full except for one spot where some young men were loitering. Brods stopped and rolled down his window to ask if they could please move so he could park, and then one of the young men put a gun on his face. He didn’t know this gunman. The gunman wasn’t even trying to rob him. The gunman said, “Ah just ge dis gun, an yu di disrespect mi.” And he pulled the trigger.

But this was Brods. In the second it took the gunman to pull the trigger, Brods hit the gun aside with his head. The shot hit the bridge of his nose. It ricocheted off the bone and exited through his eyelid. With a bloodshot eye, he did the quickest K-turn of his life and drove three miles to the hospital at night. When I reached the hospital, I saw his truck door wide open. Saw the driver’s seat stained with red, dripping from the steering wheel. So, when I saw his head heavily bandaged as he laid perfectly still in his hospital bed, I thought the worst and probably sounded like it as Brodam groggily said, “Calm dong Blaire. Yu di mek tu much naise.”

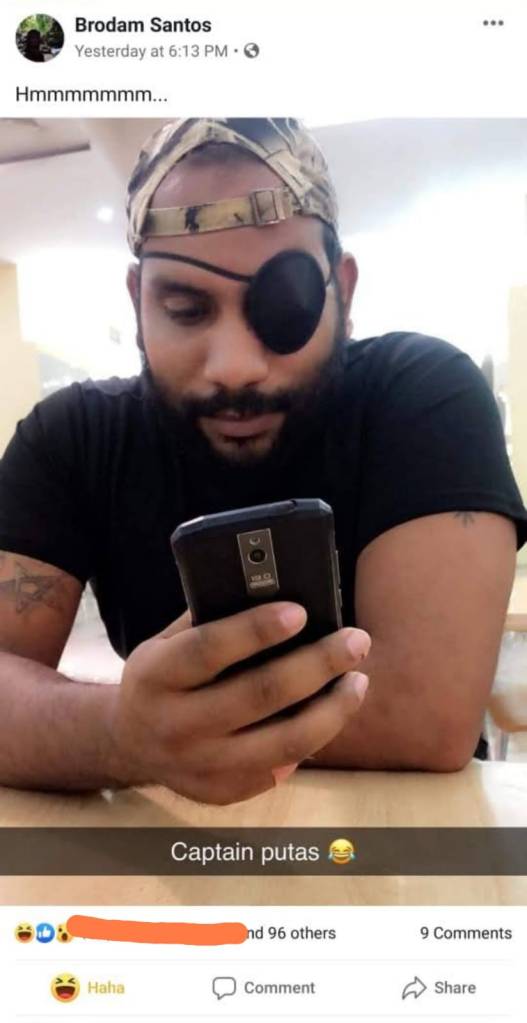

I stayed with him in the emergency room for two days, and not once did an optometrist come. “Belize only have three optometrists,” said the nurse. “And dehn de pan holiday.” His wound got infected. The skin turned black. So, our family pooled our resources and took him to Chetumal, México. The same night he arrived in Chetumal, he got emergency surgery. The following day, he put on an eye patch and then pretended to be an inappropriately named pirate captain for the next three months. This was Brods. He’d survived so much, and I was certain he would survive yet again.

I didn’t have my car. Brods had taken it to the mechanic for me the day before. So, I called my friend, Dee, and I called 911 to send an ambulance. The hospital is one street away from Brods’ house. At a slow pace, it takes less than a minute to drive the distance. I thought surely, they would be our best bet. But Dee drove about a mile to get me and Grandma, and then we headed towards Brod’s house, which is another two minutes away, and we still arrived before the ambulance. It was about 300 yards behind us, but it should have been there ages ago. He was sprawled on the grass of his front lawn. The smell of charred steak stung my lungs. He was barbecuing when it happened. His eyes were open, and I was full of hope until I realised they were not moving. I wailed like La Llorona and collapsed, but then my grandma grabbed my shoulders and shook me.

“Dis da noh taim fi cry,” she said. “Ih still have wa pulse!”

He had a faint pulse, but he was unresponsive, and the police said, “Don’t move him!” So, we waited and waited for the paramedics to stand around and do nothing. They had no sense of urgency. When they finally wheeled him into the emergency room, more than thirty minutes had passed, and the cold ground had leeched on him for too long, but this was Brods. So, I still thought he would pull through.

At the Western Regional Hospital, only one person is allowed to see the patient in the emergency room after they have been stabilised. By that time, a small crowd had come. Grandma and Domz agreed that I would be the one to go see him when the time came. As his only full-blooded sibling, I was his closest relation, and they felt that, if need be, I should be the one to make the tough medical decisions. Only eight minutes later, the doctors said, “Unu come in. Everybody can come in.” And I knew. I felt the finality, the dreaded loss.

But most of the others had never been to the emergency room before and didn’t know that this was uncharacteristic. There were not prepared. Not prepared to see red rolling from under his body, dripping onto the floor. Not prepared to see red from his open mouth while his eyes were still open. Not prepared for the way Domz would hold his head and cry. Not prepared to see Grandma, who always said she had better things to do than cry, bawl living eye water and repeat, “No. Brods. M-mi son. M-mi baybi. Yu noh dead. Y-u noh d-dead. W-why d-dehn n-neva k-kill m-me inst-tead!” until she couldn’t talk anymore.

Her blood pressure rose in tandem with her cries until she collapsed in my arms. I found a strength I don’t think I’ll possess ever again. I held her up and barked out orders at the doctors and nurses as if I were in charge.

“Bring wa chair. Bring wata. Get high blood pressha medication eena wa injection. Now.” And everything was conjured like fish at the end of Grandma’s hook.

Afterwards, I went back to Brods and held his hand, and his arm jolted, pulling me closer.

“Ih move ih han! Ih alive!” I yelled in disbelief, but it was just the rigour mortis.

When they turned him on his side to put him on a gurney bound for the morgue, I couldn’t count all the holes in his back. It was like a colander. I stopped counting at eighteen as straight, neat lines of blood flowed down his back, obscuring my view. Such order in the chaos.

Of course, it rained at the funeral. I glanced at Daddy’s grave, which Brods had built at the opposite end of the four plots we had bought just two and a half years ago. I saw the explosion of rain channelling neatly through the grout lines of its blue tiles. The wind whipped waves across the blue, and the burying ground curdled into red muck, and when Pastor Brown said, “Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust,” they splattered red clumps onto Brods’ white shirt, mimicking his shotgun wounds, and I screamed. I sank as if the ground was water—like I was going to kick up red from the bottom of a pond in Blair Atholl.

Still, I didn’t flop because Grandma pulled me up with the sharp diagonal tug of her burly hands and said, “Ah gat yu, Blaya. Ah gat yu, baybi. Ah gat yu.”

Hib Ahn Lang Shoa

Brodam Santos was a beloved member of his family and local community.

He pushed me to pursue my professional career. Every day he always asked me “how was work?” with genuine interest. He always reminded me that what I called failure was just another opportunity for growth and that starting over was another go to get it right. His mind was as big as his heart. He impacted our daughter’s life. He inserted himself into her life so magically. In 2021, the night we told her we wanted to start living together, she asked him if that means he’ll be her daddy. He told her “Yes, I’ll be your other daddy.” She said “Yay, I never had a real daddy before.” That was the first time I saw Brodam taken aback. He had no response but to embrace her. She couldn’t wait to see the house so that same night we went over, and all all three of us slept in his bed. He gave her a strong sense of love, support, and security. We agreed that our next journey would be together,and had our whole life planned, but in true Brodam fashion, he had to go and scope it out first.

D.D., FiancE

At the last meeting I had with Brods he looked at me, and

tears began cascading down his cheeks. He said, “Mom, I love you, you know. I love you. I love you! Love you” Over and over, with passion. He had never expressed love to me like that. It was usually, ‘I love you, babe.’ ‘I love you too, ma.’I know I was one of his inspirations because I don’t let anything keep me back either. You could knock me down ten times, and I will come back, and Brods adapted that drive. The world is nothing. You can overcome. Although his life may seem too short, as I’ve expressed before, Brodam has lived a lifetime in thirty years. Even the Messiah only lived 33 years before he was crucified, and he fulfilled all that he was destined to fulfil. Brodam has left an indelible mark of gratitude, forgiveness, and love for his fellow men. If Brodam could say one thing, it would probably be, “Get up. You can overcome.”

c.d., Mom

He loved cats. He loved all animals, but especially cats. And he was great with kids. As a baby, his niece would drink her baba and fall asleep on Brodam’s chest. Whenever she visited Belize, she enthusiastically joined his shopping trips at Builders Hardware. In exchange, he would entertain her at her tea parties.

C.z., Sister

I had him listed as my first emergency contact, before our mommy, because I just knew that if anything, my big breda would come. He would be there. He would rescue me like he always did when we were kids.

Blaire Santos, Sister

He staged trick or treat for the children in the neighbourhood. He came to my house and said, “Some pikni wah pass and unu wah give dehn sweet.” He then handed me a huge bag of candy. He went door to door. Hilarious!

J.G., Cousin, NeighBour

He was silly and I mean that in the best way possible. We were playing apples to apples, a game you have to come up with nouns to match adjectives. Blaire was the judge for that round. She picked the adjective “opaque.” I said mountain, the other person said wall. Solid options. Brodam said, “big truck.” Blaire cackle! and said, “But ih have window.” He said, “When yu de pan the road di drive behind wa big truck, you can’t see nothing.” and Blaire seh, “No wonder you crash so much.” Best memories.

C.J., Friend

So the Car Show started in 2017, I had a car wash called Executive Touch Auto Wash and I always washed nice vehicles. So I decided to do a Car Show called Executive Touch Auto Show, which later evolved to Press Gas. He always supported my car wash and the show. Brodam really loved basically anything with a motor in it. Since he does Construction, he always had the right tools, equipment and big truck to help when he can. Since the first car show, he always helped out with a generator, and I always ask him for that every year, until I didn’t have to ask lol. Each year the show gets bigger and he wants to help out more, then he became an official sponsor with BVS Industrial Solutions last year in 2022. I get sponsors to assist with expenses and prizes. Brodam always wanted to be the biggest sponsor, but never mi want give all the cash lol he seh I the cut into his beer money 🤦🏻♂ so he always give $500 and some labor to be a Platinum Sponsor. Last year he built the bridge so we can have a second entrance to the spot we use for the car show. He was a really good person and wasn’t into anything bad. I know that for a fact, he was very kind and loving. Loves trucks, and weird music lol always ready for anything manly, mudding, fishing, BBQ, beers, women 😋 but he settled down with Domz.

K.B. Friend

He was our saviour. One time my mom ran out of oxygen, which she needs, and it was in the middle of the night and nowhere was open. On top of that, the hospital didn’t have any! I didn’t know what to do. Same time my kids called Brodam. They were good friends. Brodam show up not too long after with some oxygen tank. He went to find the owner of the hardware store and got the oxygen. He saved my ma life.

E.F., Parent of friends

Tomorrow will be better.

Brodam Santos, July 25, 2023

Want to add to his story? Comment below ♥

The SOCIAL Amnesia

Brods suffered over eighteen wounds from two shotgun strikes. He would have needed immediate surgery to have a chance at survival, which the Western Regional Hospital is unable to perform. This is in the capital city; however, the only hospitals remotely equipped to treat shotgun

wounds in the country are fifty miles away in Belize City, and only one is public. The other two charge over $5,000.00 US a night.

Brods was an innocent victim of Belize’s epidemic of gun violence and atrocious health care system. At a mere thirty, just three days before our fishing trip, just six days before Grandma’s birthday, just two months before his wedding, he was killed for nothing.

All now, the investigation has turned up nothing, but police speculate that someone at his barbecue is the brother of the intended target, and, in the dim light of night, he looked like the person whom the gunmen were after. So, it seems stray bullets from a case of mistaken identity killed my brother. It is one appalling irony after another. I don’t know where to place my anger. Who is responsible?

Here are some news reports circulating about his murder:

Learn More

19 Things You Can Do To Stop Gun Violence

How the 1996 Dunblane Massacre Pushed the U.K. to Enact Stricter Gun Laws

Lack of Gun Industry Accountability

Understanding global gun violence, and how to control it

Belize works to reduce armed violence and crimes involving firearms – UNLIREC

Leave a comment