Prefer to read?

The island of Saint Lucia lies between the turbulent waters of the Atlantic Ocean and the calm waves of the Caribbean Sea. Situated in the middle of the Eastern Caribbean island chain, Saint Lucia has been a transitory point for hundreds of years during the precolonial and colonial periods.

It was used by Kalinago hunters island hopping for subsistence and later by the French and the British for their imperialist endeavours.

Saint Lucia’s geographical, political, and social intermediary characteristics have impacted its social landscape, creating a unique creolised expression of various cultures and ethnicities. The effects of which can be found most poignantly in Saint Lucia’s most widely spoken language: Kwéyòl.

Saint Lucian Kwéyòl is an amalgam of various languages that evidence its colonial past. Kwéyòl comprises a predominantly French vocabulary, with influences from African and Amerindian languages. The African influence is most notably expressed in Kwéyòl’s grammar, as the structure of the language is quite similar to West African languages.

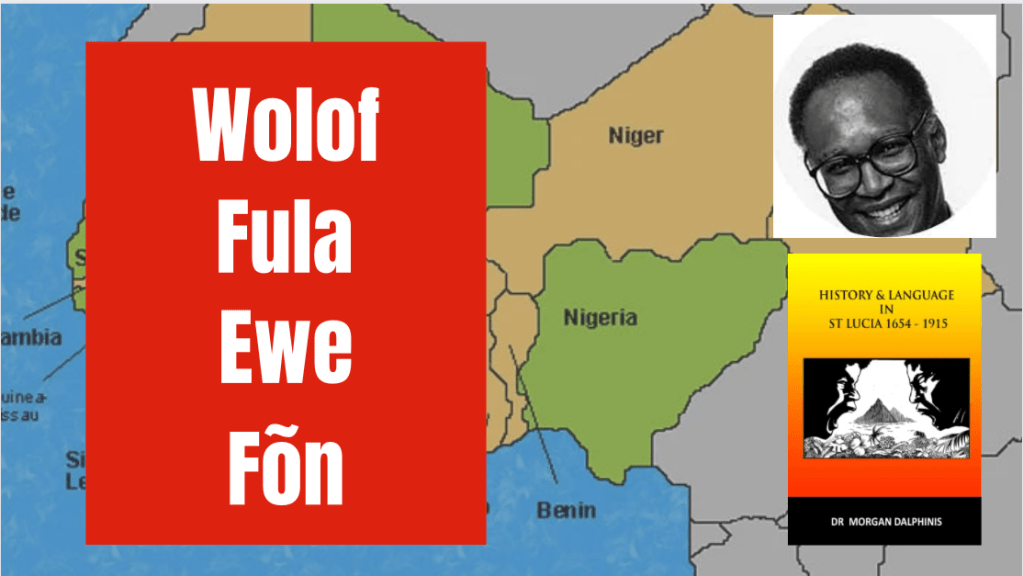

Linguistic historian Morgan Dalphinis suggests that the linguistic influence of West African languages on Saint Lucian Kwéyòl is credited to Senegambian languages such as Wolof and Fula and Dahomey languages like Ewe and Fõn.

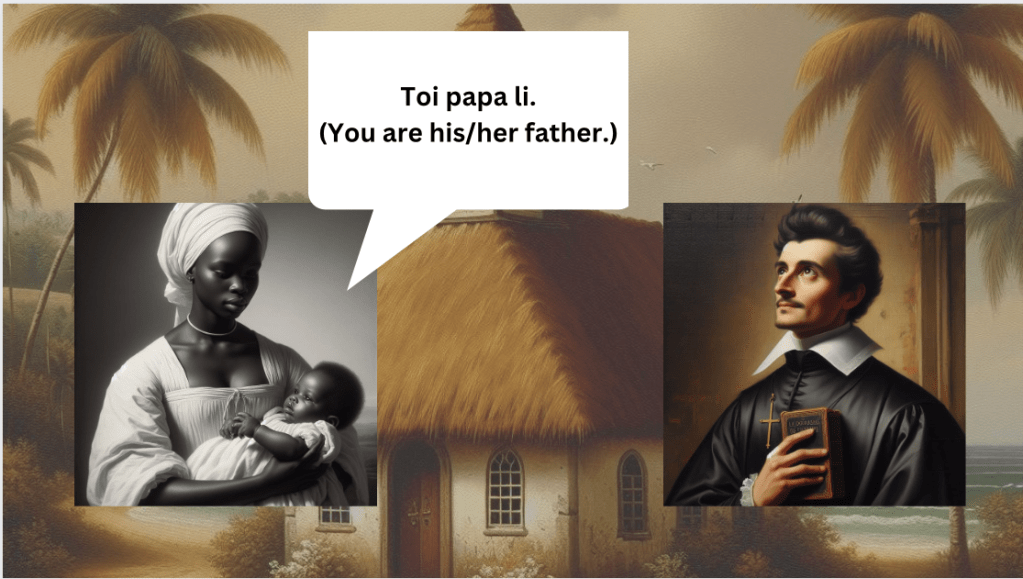

One of the oldest references to Kwéyòl was in 1695 in a written account by French missionary Jean Baptiste Labat of an enslaved woman speaking to a priest about her child:

“Toi papa li” – “You are his/her father.”

There is a prominent French influence, with the ‘toi’ signifying the French possessive form of ‘you’ and ‘papa’, an informal form of father.

The pronoun ‘li’ is also of French origin but is a Kalinago variation of the French indirect object pronoun ‘lui’, arising from trading interactions between the two groups.

What is interesting is the existence and position of the word ‘li’, which does not follow French syntactical order. It evidences a West African influence reflected in the Kwéyòl Saint Lucians speak today.

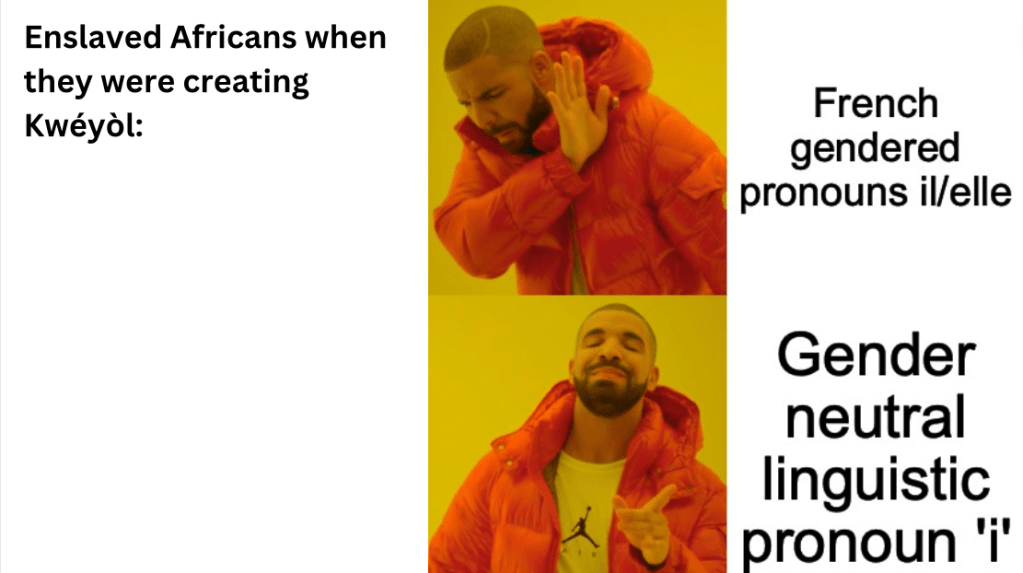

The pronoun ‘i’ is a convergence of the French ‘il’ and is a counterpart to ‘li’. Despite their origins from masculine French pronouns, they both mean the same thing: he/she/it.

This lack of deviation with the third-person singular pronoun is a feature of West African languages. For example, Wolof, Fula and Ewe all have one word for the third person singular pronoun that signifies he/she/it.

Wolof: Moom – He/she/it

Fulfulde: Hanko – He/she/it

Ewe: É – He/she/it

This lack of grammatical gender marks Kwéyòl as a gender-neutral language. Despite French containing binary pronouns, enslaved Africans opted to maintain the gender-neutral linguistic structure of their West African languages.

Even the subsequent English influence on Kwéyòl has not disrupted the genderlessness of the language, proving impervious to the imposition of the Western concept of gender binaries. The insistence on preserving gender-neutral pronouns in a language they were forced to create is a noteworthy form of rebellion as it is a covert example of linguistic preservation.

Sources:

Dalphinis, Morgan. African language influences in Creoles Lexically Based on Portuguese, English and French, with Special Reference to Casamance Kriul, Gambian Krio and St. Lucian Patwa. University of London (United Kingdom), 1981.

Dalphinis, Morgan. History and Language in St. Lucia 1654-1915. GLOM Publications, 2019.

Leave a comment