Speculating on diversity in media.

-Written by Dominic Ramsay

I had a particularly interesting thought experiment the other day.

I, a black man, was speaking to my girlfriend, a black woman, when I posed a hypothetical question that on the surface seemed like a simple question but as we spoke, we realised it contained deeper more complicated discussion points.

My question was posed as such:

‘Imagine there is a little 8-year-old white boy. This 8 year old white boy is very excited about the upcoming Halloween season and he says to you “This Halloween, I wanna dress-up as my favourite superhero! I wanna be Black Panther!”

Now you being the level-headed adult try to stifle your reaction to this child’s desire, but your curiosity gets the better of you. You can’t help but simply ask him “Why do you want to be Black Panther?” To which this little boy, with innocence in his eyes says to you “He’s just so cool! I loved the part when he does all the flips and jumps and how he fights and how he’s so brave…”

As he goes on you realise quickly that there is no part of this white boy’s reasoning in which he’ll say black panther is cool because he’s a cool black guy. This child does not understand race issues yet.

To which my girlfriend interjected and said that she would have no issue with this, and she would be happy to tell this kid to dress up as Black Panther.

To which I said, that might be the right thing to do, but that creates some dilemmas on what Black Panther means as a character and as an icon for black people.

Welcome to the complicated world of diversity in media, where every creative action and decision becomes a tightrope walk between offending different groups of people.

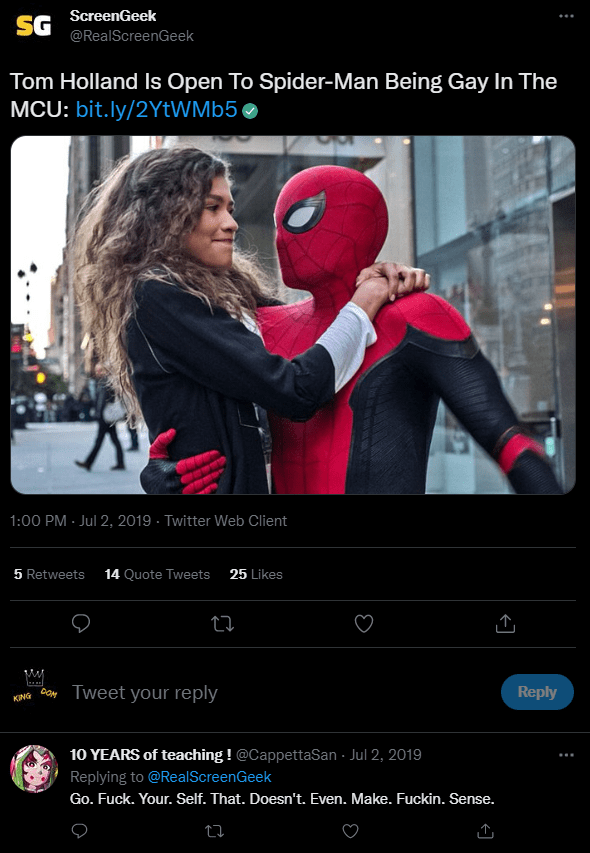

My reignited interest in following this debate started when I had found the youtuber, Veridis Joe and watched his video essay simple titled ‘Diversity Isn’t Political’. In it he was addressing the controversy sparked from the online rumour that Marvel Studios was considering for their films to slightly change Spider-Man’s character by changing his sexuality from a straight man to a bi-sexual man and giving him a boyfriend for a new love interest. Some die-hard Marvel movie fans expressed outrage on the internet over this consideration arguing that such a change is unnecessary virtue signalling to appease ‘the gays’.

Veridis Joe challenges these perspectives by arguing that “See the term virtue signaling is used by a lot of people when they just see progressive media and have a problem with it. That also goes for when they say its political. Having a diverse group of characters in your current media isn’t political it’s a sign of respect to all the people who watch your shit and it’s just normal to include people who exist and have them represented because you know, they exist.”

While I do understand where this sentiment is coming from, I have to respectfully disagree because a statement acknowledging the existence of underrepresented or oppressed people is in itself a political statement. The creative decision behind choosing what should be represented and what should be omitted creates a lasting impression on the audience for the group of people being represented regardless of if it’s a positive or negative depiction. This is why I believe diverse representation is generally considered to be an empowerment tool for minority groups as a positive representation becomes a good reflection on that community as a whole.

However, this begins to beg the question ‘What is a positive representation?’

Going back to my Black Panther Halloween costume example, if we replace the race with the more contextually appropriate, black boy then a different connotation arises from his desire to be Black Panther. By virtue of the boy and the character sharing the same skin tone, societally speaking we view Black Panther the character as having a different, more impactful meaning to the black child than to the white one. Even though realistically speaking, the black child may have the exact same reasons of admiration for Black Panther as the white one. There is an understanding that the black child can more easily relate himself to the character because he sees someone who looks like him doing impressive things and by simple deductive reasoning, infers that it is more possible for him to do impressive things too.

The idea of the exact same media having different interpretations by different groups of people is an argument supported by cultural theorist Manthia Diawara who in his article titled ‘Black Spectatorship: Problems of Identification and Resistance’ he expresses that “…the components of ‘difference’ among elements of race, gender and sexuality give rise to different readings of the same material.” (Diawara 67)

Therefore, it’s understandable why Black Panther is expected to mean so much to the black boy and why the white boy is allowed to stop at the surface level of just enjoying a movie.

But in there lies an issue in translating the cultural significance of characters in media. If the white child is equally allowed to enjoy the character of Black Panther as the black child but is not expected to appreciate the significance of the representation because it’s not for his people, then can we really say this representation is doing its job correctly?

How can Black Panther be a culturally significant racial icon for black people if he can be reduced to being viewed as ‘just another cool superhero’? If Black Panther were more overt in proclaiming that he is an icon exclusively for the empowerment of black children, then that alienates white audiences who will thusly ignore the messages of representation being delivered. Hence, the only group receiving the message that ‘black people are great’ are black people themselves and then the message is no longer informative because it is preaching to the choir.

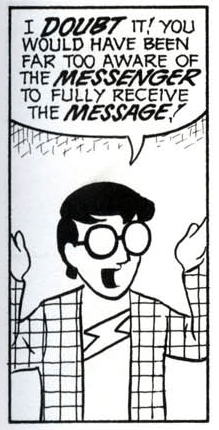

Comics illustrator and writer, Scott McCloud touches on the dilemma of conveying messages through representation via characters. McCloud infers that the more generic the messenger appears, the more receptive the audience becomes to understanding the message and vice versa, the more specific the messenger appears, the narrower the reach of the message becomes. This is summed up in the illustrations McCloud created in his book ‘Understanding Comics’.

However, McCloud’s perspective makes me want to return to my question of ‘What is good representation?’ Because we live in the world where Black Panther was written as a generic superhero and thusly the hypothetical white boy who admires him, actually exists for many white children. Can we argue that this version of the character is good representation?

I would not say that the message of what Black Panther is supposed to be is lost, but rather argue that it is unclear.

The duality of the character’s existence as both a black icon and generic superhero muddle the message of who should be empowered, black kids or all kids? It’s as cultural theorist Stuart Hall explained in his lecture called ‘Negotiating Caribbean Identities’ “…questions of identity are always questions about representation. They are always questions about the invention, not simply the discovery of tradition. They are always exercises in selective memory and they almost always involve the silencing of something in order to allow something else to speak.” (Hall)

If these white boys get to feel empowered by Black Panther, then suddenly being black becomes less important and likewise if these black boys are supposed to feel empowered because Black Panther is black then the white boys can’t relate to him and he becomes the ‘black’ superhero.

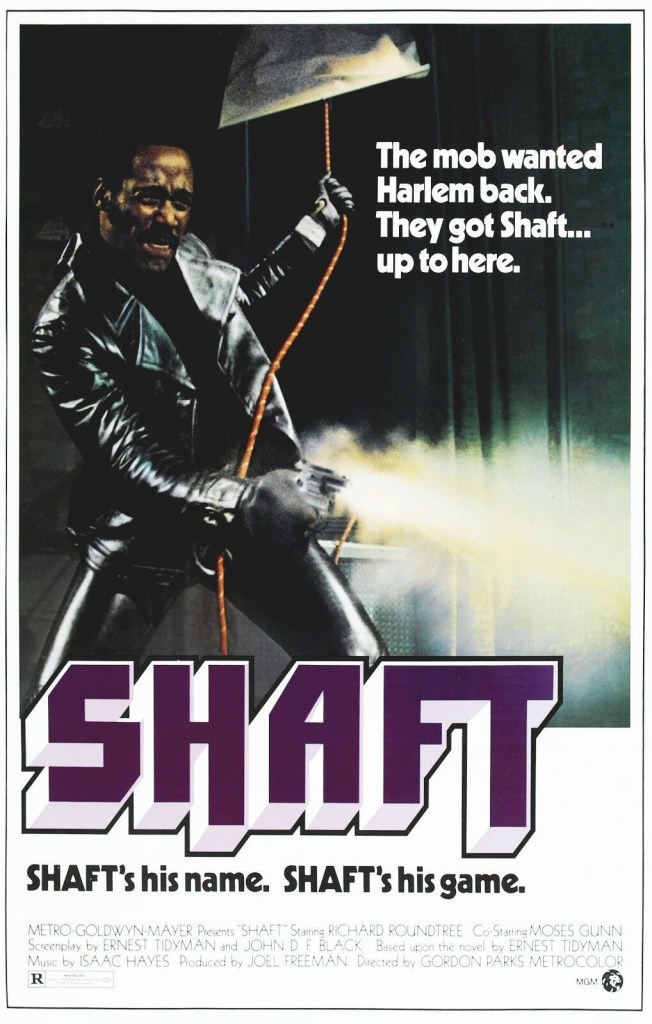

I argue that even if the representation is viewed positively by outsiders to the message, the margin for error of misrepresentation/bad representation is still present which ultimately does more harm for the people being represented. Case and point, look to the black exploitation films of the 1970’s.

From Shaft, to Dolemite, to Foxy Brown, these depictions of black people were considered ‘cool’ in the cultural space of the 1970s, but they mostly comprised of films with problematic leads who were either misogynistic gangster men or objectified sexy ladies. What were considered ‘cool’ representations of black people then are what we now call exploitation films.

This is why I call it a tightrope walk of representation because so many heavy factors such as realism, positivity and relatability among other things have to be considered for a ‘good’ representation; a title of which I still do not have an exact definition.

This dilemma is one which I do not think can be so easily solved as definitions of what is morally acceptable and not are constantly shifting and changing with the times. In truth, there will be more trial and error of representative characters, but as western media continues to experiment with the precise formula for these characters then I believe we grow closer to getting the balance right.

To lighten the mood I’d like to leave a clip of Donald Glover’s stand-up special Weirdo, where he addresses his own personal controversy when he was recommended to play Spider-Man himself. I believe this clip does well in summing up the issues of representation.

Works Cited

Diawara, Manthia. “Black Spectatorship: Problems of Identification and Resistance” Screen, vol. 29, no. 4 Autumn 1988, pp. 67-79, https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/29.4.66

Hall, Stuart. “Negotiating Caribbean Identities” 1995, Lecture

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Harperperennial, 1994

Leave a comment