By Kandice Thompson

Gibrey Allen is the director of the 2020 film Right Near the Beach which examines Jamaica’s cultural approach to sexuality and grief. The film follows Miles after the loss of his son Jeff to a brutal hate crime.

Allen also plays the Miles’ son Mike who returns to Jamaica for his brother’s funeral, and we see the two men ensconced in their grief, alone together.

I had the opportunity to speak with Gibrey about his film and our conversation proved to be fruitful and thought provoking.

Voice of the Filmmaker vs the Film

In our talk, we spoke about the responsibility of creatives and being mindful of who and what we try to present on film. It had me thinking, is the voice of the filmmaker present? How does it function within the film itself? Is it conflicting? Too loud or subtle and guiding? What should the audience take away? I have become grounded in the fact that we in this class are Jamaicans now writing on Jamaican Voices: Real and/or imagined. How will our own voices hinder our objectives? But who better to write about Jamaicans than us? We don’t want to be voiceless, sounding monotonous and far removed from our work. How does objectivity come into play with creative non-fiction?

Representation and Authenticity

On the subject of being mindful and straddling the line of creative freedom and misrepresentation/stereotyping in media, we spoke about who gets the privilege to represent Jamaica and Jamaicans onscreen and how authentic that may be. Allen is heavily invested in Jamaican narratives in film but sits at an intersection of sorts, a Jamaican but an American immigrant. What kind of stories can he tell? Should he tell? Right Near the Beach, for instance offers a stunning portrayal of men’s mental health and the social repercussions of any sexual expression that deviates from what is acceptable for men. The film is a quiet one set in the countryside and follows Miles Jacobs as he grieves the loss of his son who was beaten to death on the suspicion that he was gay.

I think he did an amazing job depicting a quintessential Jamaican countryman in Miles’ taciturn manner and stoic disposition. His silence becomes loud set against the stillness of the film. With little dialogue, soundscape of the countryside and artful shot composition that does the work to drive the narrative rather than spectacle and glamour. This kind of Jamaica is what I know but it isn’t something I had ever seen on film before. I was so moved, it felt like me in a sense, I could see my own family in that kitchen, my uncle in that field, me being annoyed and smashing that radio, the story was so raw and honest and Jamaican. Allen wrote from his own unique perspective that is informed by the Jamaica he knew as a local (and that snapshot remains in his mind’s eye) alongside the Jamaica he knows now. I think the feel of authenticity translated because he presented what he knew rather than pre-packaged stereotypes

Jamaican-ness?

We, in the mainstream, are subjected to stories of poverty, violence and exploitation. While we can appreciate and acknowledge the space for films like Dancehall Queen, The Harder They Come, Smile Orange, Ghett’a Life and Shottas, where is the variety? Who are the people behind these films? In many cases, it is often people who are removed from the narratives they present to us (the masses), and a lot gets lost in translation as there are limits to what they can accurately portray. Yet, these are all we look to when we discuss Jamaican film, and these creatives are the sole authority. Is what they represent truly and authentically Jamaican? There are certainly elements that are relatable and entertaining, and we love it but is that all we have to offer? Do we love it because that’s all we have access to?

What are rules of engagement and limits on sexual expression for men in Jamaica? Be straight, be tough (no tears) and sexually aggressive, dominant, loudly macho, no? Allen questions and subtly subverts traditional expressions of manhood, what that looks like, what men can give voice to. This is a male-driven film, which he acknowledges, but felt it necessary to highlight them in this way. Women’s voices are present to underscore male vulnerability but not overtly distinct. It also looks at the queer voice, how it is muffled in our society, but we seem to hyperfocus on it all the same.

Right Near the Beach dissects how we express grief, traditionally, the rituals and processes. What is expected and accepted? Loud, passionate outbursts of emotion – bawling, anger, partying. sharing stories – communal grief. But what about the quiet anguish, isolation, the role of rumours and ostracization? We watch as Miles’ connection to his rural community is slowly untethered and he is ousted from the community because of the speculation that his murdered son is gay and he too receives homophobic backlash, but Allen simply asks, “What if it was your kid?”

So Jamaican-ness, Is it quantifiable? I don’t know if I can in any certain terms quantify it right now. So, I have to be mindful of my own voice and biases usurping that authenticity and realness that I’m searching for in uncovering these voices – real and imagined and presenting them. It’s attractive to go for the marginalized voices because it feels good to be giving a platform to and shining a spotlight on those that have been overlooked and examining why we’re overlooking them and how much they influence/feed into our culture. I think of Shebada’s popularity (and infamy) and influence on many male social media comedians and influencers who don wigs or reach for female characters often.

Snapshots of the Now

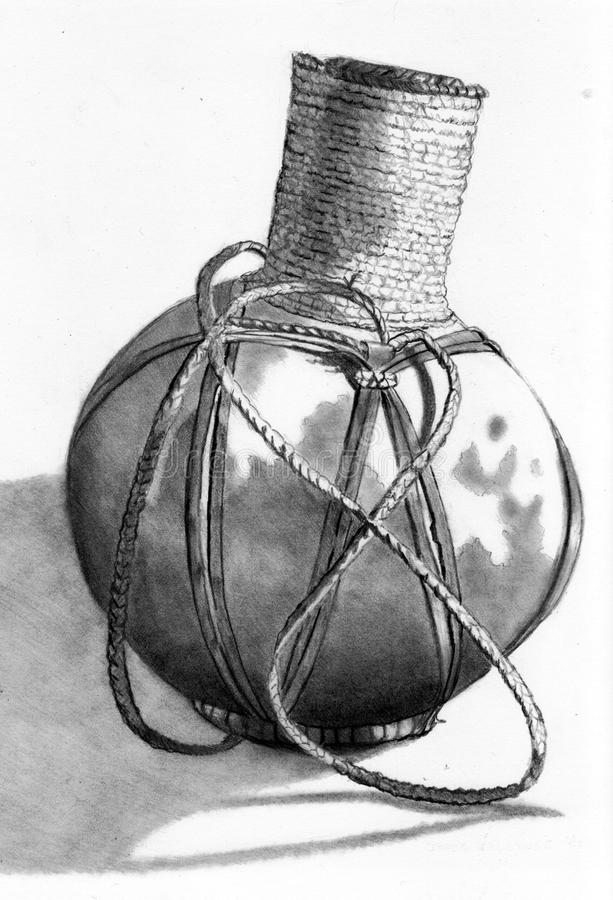

The conversation had me considering the power of film, how it is disseminated (who gets access, who is the audience?), what we can encapsulate in this type of media and linking it back to Digital Humanities and dLOC’s efforts in preservation. There are real world implications to our work, cultural impact – passing on, teaching, holding knowledge, storing, retention. I recall the bonding scene in Right Near the Beach between Miles and Mike, a sort of ethno-botanical lesion, when Miles sings a folk song that he didn’t know was listing plants and their medicinal uses and his father walking through the bush and teaching him, that clip and by extension our digital work serves as a calabash of knowledge and cultural identity.

Leave a comment