Dubstep as the sound for the sonically innovative or the musically colonised?

An essay written by Dominic Ramsay

The identity I feel most comfortable describing myself as is a creative Black person.

I purposely choose those words in that order because while I am quite proud of my ethnicity and the racial history of a group of people I feel relatability towards, I do not believe that my race, as important as it is, should be the most forefront aspect of my identity.

I consider myself creative and therefore open-minded and appreciative of art forms that are niche, unorthodox and plainly put weird. This has led me to hold what some would consider strange tastes for a black person, like how my favourite music genre is Dubstep, colloquially deemed to be White people’s music.

It has been difficult to summarize to strangers how Dubstep uniquely appeals to me, especially with the critique of how strange it sounds serving as a barrier to entry for understanding. However, conveniently I stumbled across a video that encompasses the appeal and critiques of Dubstep holistically, that video being: ALL MY HOMIES HATE SKRILLEX | A STORY ABOUT WHAT HAPPENED TO DUBSTEP.

This was created by a youtuber I had never heard of before named Timbah on Toast. The relative anonymity of the source granted by my ignorance made it all the more enticing to hear this unknown perspective. What I was greeted with by opening this video was a 52-minute-long dissection of the niche genre of music that I considered to be my absolute favourite genre and a thorough explanation as to why Skrillex, A.K.A my one of my favourite Dubstep artists of all time, A.K.A my favourite artist of all time was the worst thing to happen to the genre’s culture.

Understandably I was very offended at the cleverness of that clickbait title. However, this video concept came from the mind of someone who also claimed to have a genuine love for this obscure and polarizing genre so I was admittedly a bit curious to see how someone with my similar interests could turn out to have such a drastically different perspective on the art form.

So I sat and I watched. About 1 hour later I found out I really loved that video…

…But I have a few objections to say.

Firstly, I must commend him for his concise recount on the history of Dubstep. Dubstep as a music genre is relatively very young compared to other genres. Having really picked up recognition in the mid to late 00’s and claiming an identity of an ‘underground’ genre, the history of Dubstep’s genesis was not properly recorded and documented, hence this video actually serves as a very important resource in tracking the genre’s history. The origins of Dubstep stem from the United Kingdom and within the video Timbah on Toast, speaking in the first person recounts the story of Dubstep’s origins from the perspective of his youth growing up in the U.K breakdancing scene where black music, typically American hip hop was integral to that scene. He then recounts that one day, through a friend he met while breakdancing, he was introduced to an early Dubstep song and was immediately hooked on the genre.

But the Dubstep he was listening to admittedly sounds very different to the sounds typically associated with the genre now.

As he puts it in the video

Dubstep “…has acquired the meaning of being something other than a genre. It’s more like a ubiquitous oral shorthand for absurdity that everyone immediately recognizes as a shrieking piercing overcompressed noise that’s played for about two to three seconds in adverts or YouTube videos. Enough time for a joke to land or the youtuber to pull a silly face…before the video cuts to something else. Dubstep is not just the butt of a lot of jokes, Dubstep literally is a joke.” -Timbah on Toast

While it is quite a harsh deconstruction of the music, he is not totally inaccurate. But that criticism is more so based on the general public perception of Dubstep rather than the nuances of the genre as it is now or the history of how it came to be perceived as such. The sound and aesthetic of Dubstep as it was originally created in the early-00’s sounds practically unrecognizable to the ‘overcompressed noise’ of today.

DJ Hatcha, a popular DJ from South London is credited with being the progenitor of Dubstep. Coming from a history of playing UK Garage music, a very popular and very black musical genre, he took the sonic structural foundations of garage and slowed it down to a 2-step beat. Then he added layers of low-tone basslines which reverberated sound systems like the Reggae artists in Jamaica would emulate for the ‘Dub-style’ and eventually DJ Hatcha would coin the term as ‘Dubby 2-step garage’ or to make it more simple “Dubstep”.

The sounds of Dubstep began to catch the attention of the South London and Brixton youth who primarily comprised of second and third-generation Jamaican immigrants. Perhaps the unique U.K origin mixed with aesthetic roots of the sound tying back to a culture familiar but not entirely experienced by these adolescents was something that struck an very unique chord for them. Nonetheless, with the influx of this newfound audience, the identity of Dubstep began to take form as a new underground U.K sound for black Caribbean kids and the sound shifted to overtly appeal to them.

Soon enough the people who would eventually become the forerunners of the genre would make sure that the blackness of the scene’s origin was worn on its sleeve. People like Mala would perform with their Rastafarian dreadlocks with songs that played traditional African drums playing during the bridge: Mala – Changes

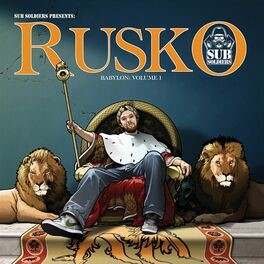

Then there were people like Rusko who heavily incorporated Rastafarian imagery of Zionism in the artwork for his album titled: Babylon: Volume 1

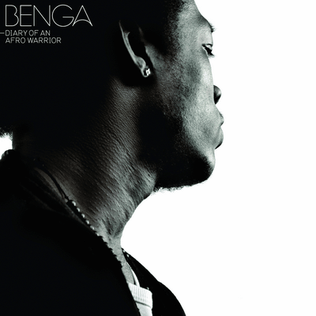

And let it not be overlooked the most overt instance of Blackness in early Dubstep, by one of the most influential Dubstep producers for the genre: Benga, who literally titled his seminal work: Diary Of An Afro Warrior

At this point we are approaching the late 00’s and two things should be made of note. 1) Dubstep is now approaching the cusp of mainstream recognition and 2) While it was very obviously portraying itself as black youth music, there was no racial gatekeeping to who could produce Dubstep hence there was an even balance between black and white Dubstep producers. Both of these things changed drastically in the 2010’s.

By 2010 with Dubstep being more regularly played in U.K nightclubs, the underground aesthetic of the genre was phased out and in becoming mainstream began to be exported overseas and recreated by North American producers and being consumed by primarily white Americans. Concurrently within the U.K the sound of Dubstep was entering a transitionary period from more subtly low-frequency basslines that could only be appreciated on large club sound systems, to more in-your-face, mid-tone heavy basslines that were aggressive enough to be heard clearly on simpler, more consumer-friendly products like Ipods and cell phones.

With the change in sound happening right as it was being exported to North America and consumed by white Americans, these new producers began interpreting the sound of Dubstep as more aggressive than before as highlighted by Canadian producers, Zeds Dead in their song ‘Rude Boy’ : Zeds Dead – Rude Boy [HD]

To the ears and fears of the original Dubstep community this tonal shift was exacerbated when Sonny Moore, former frontman and vocalist to heavy metal band ‘From First To Last’ began his solo career by venturing into electronic music, eventually making his own brand of Dubstep and releasing the now certified double platinum EP titled ‘Scary Monsters And Nice Sprites’. His genre blending of the new aggressive Dubstep style fused well with his heavy metal background and created an EP whose lead single now forms the basis from which all general conceptions of Dubstep now stem from:

Skrillex – Scary Monsters And Nice Sprites (Official Audio)

By the fact that the general consensus is that modern Dubstep comprises largely ‘Skrillex-wannabes’ based off of my explanation of the genre’s history some would accuse Dubstep’s newfound global audience of whitewashing and culturally appropriating a budding black artform. To this, I ask, ‘Why can’t it be another progression of the art’?

On the surface, it may be simple to label it as whitewashed, but as mentioned earlier, this overlooks the nuances of the actual content of the genre as it is now. The recognition of the genre’s Jamaican roots remained as ever-present motifs and aesthetics of the new style as it mixes with the new aggressive sound. For example, songs like Major Lazer’s ‘Jah No Partial’ make reference to messages renouncing Babylonian corruption referencing the popular Reggae and Dub music motif: Major Lazer – Jah No Partial (ft Flux Pavilion) [OFFICIAL HQ LYRIC VIDEO]

While a song like Cookie Monsta’s ‘Soundboy’ in both song title and instrumental arrangement makes reference to the sound-clash culture that is a staple to the Jamaican Dancehall scene: Cookie Monsta – Soundboy

Perhaps most pertinent to recount may be the instance where how Skrillex, who has been blamed as the source for the bastardization of Dubstep, appreciated the roots of Dubstep so much to create a Dubstep song in his style which sourced the talents of arguably the most culturally significant Reggae artist of the modern era, Damian ‘Jr Gong’ Marley. They then created the song that has become one of the most popular songs of both men’s careers: Skrillex & Damian “Jr Gong” Marley – “Make It Bun Dem” [Audio]

With all I have raised thus far in speaking about the intricacies of this under-documented art form I hope that this creates new appreciation for the genre or at least makes the mind of a creative black person more understandable.

Here are some of the links used for gathering information in this essay:

https://web.archive.org/web/20120112122021/http://www.imorecords.co.uk/dubstep/hatcha-biography/

-Dominic Ramsay

Leave a comment